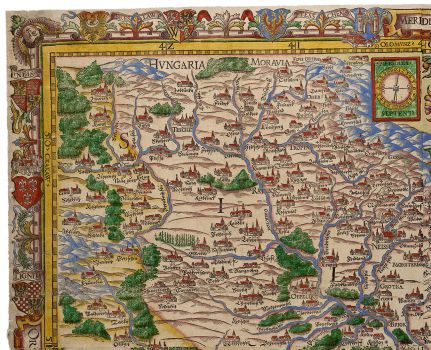

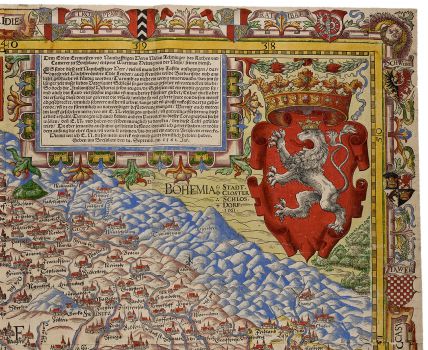

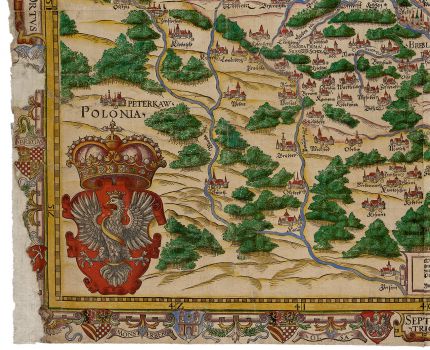

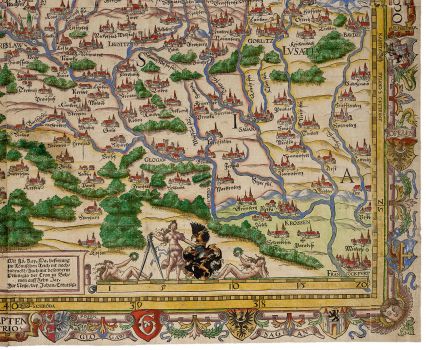

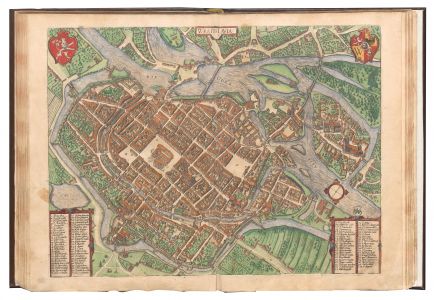

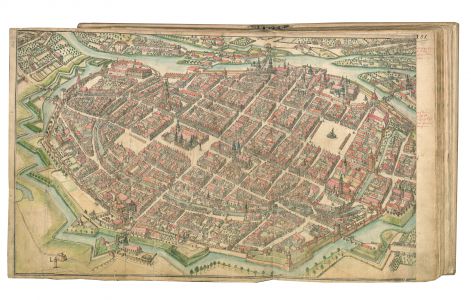

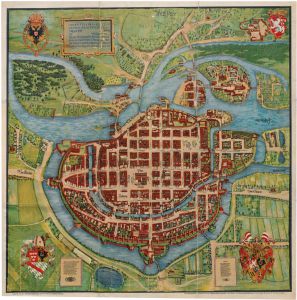

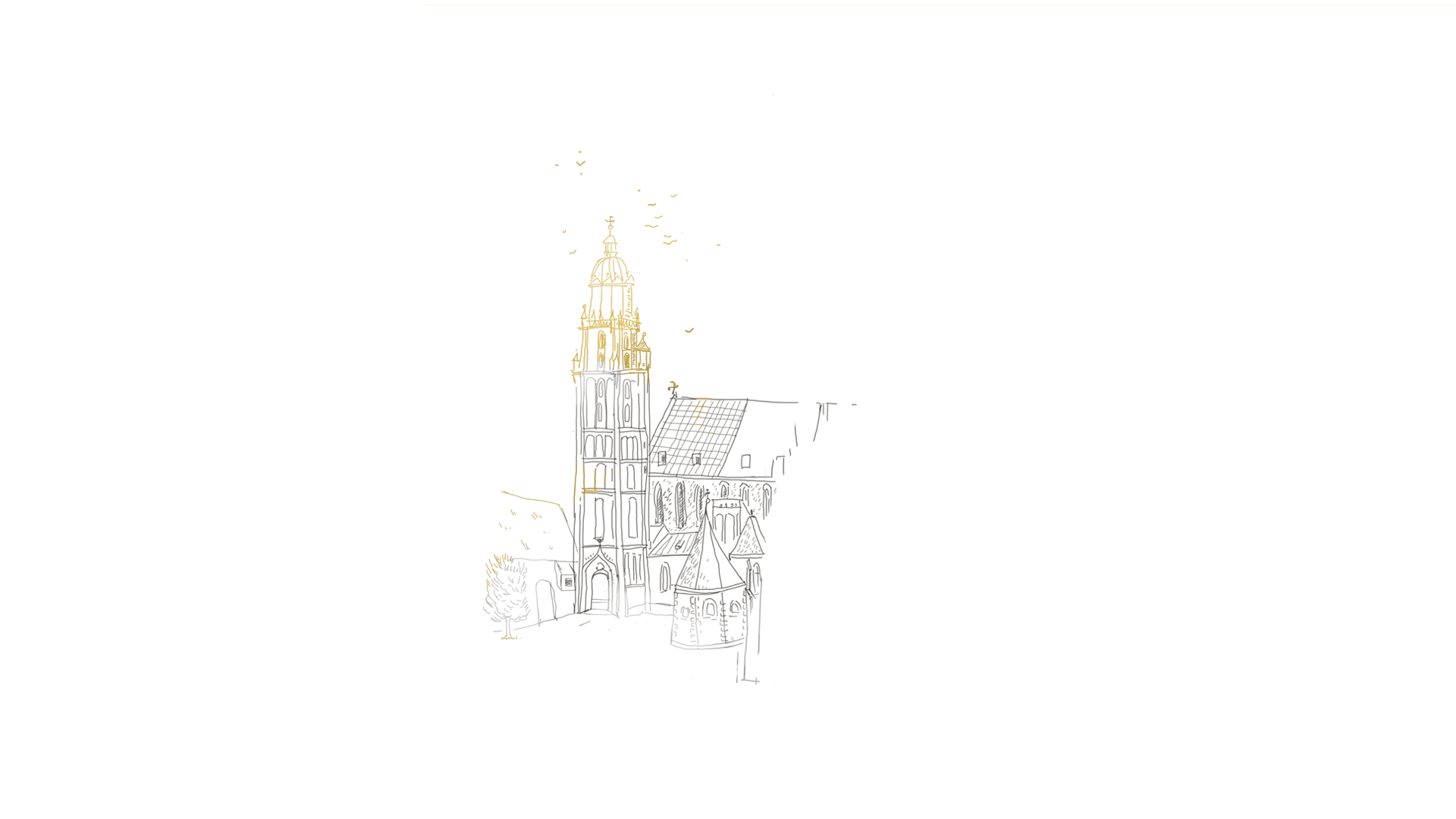

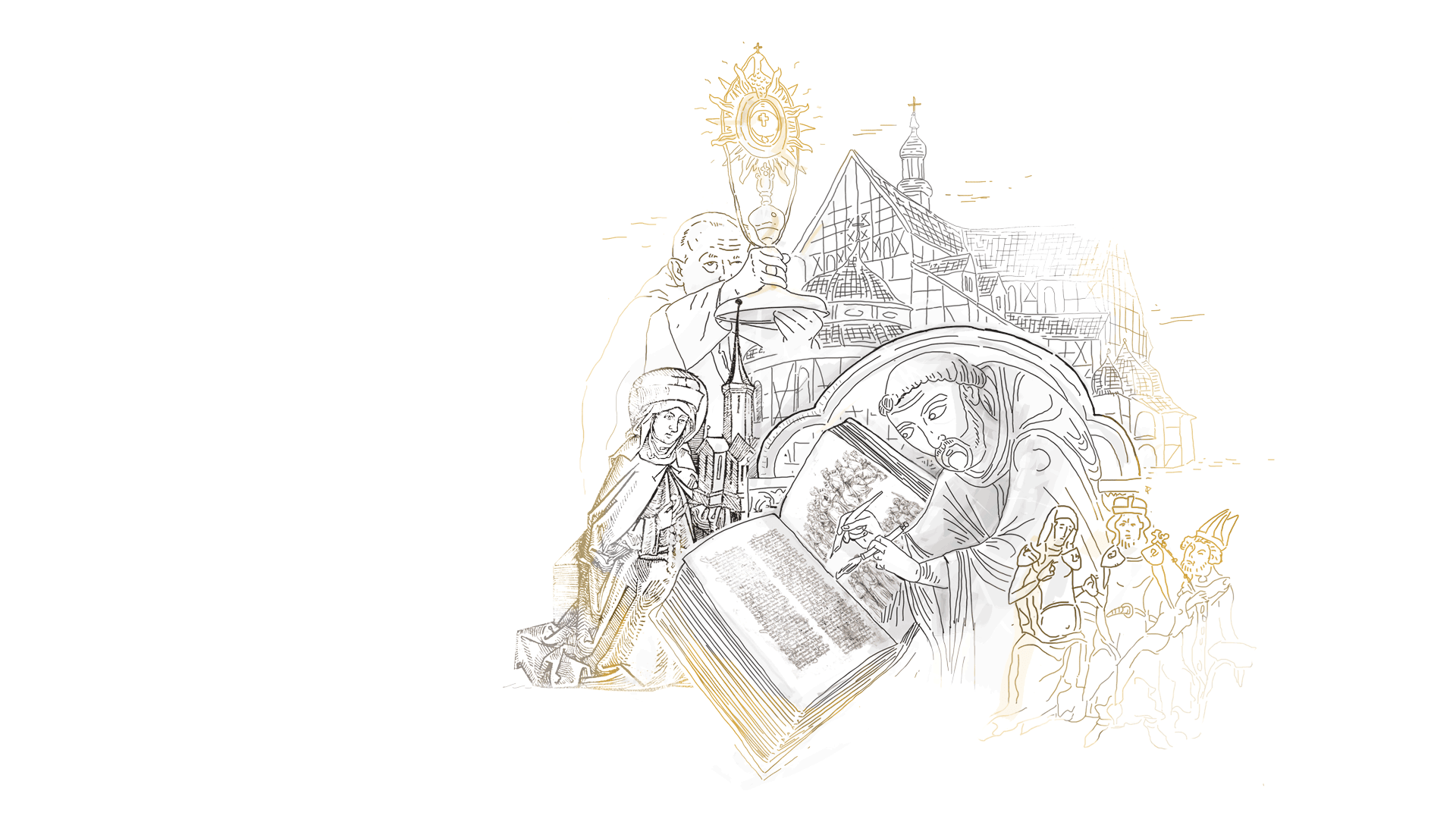

Wrocław, the capital of the Lower Silesia region, is the fourth largest city in Poland, with more than 630 thousand residents living within an area stretching over 293 square kilometres. It was established in the 10th century on islands on the Oder River, an act that provided its security and unique character. Two main communication routes of central Europe crossed here: the old Amber Road connecting Mediterranean states with the Baltic Sea, and the Royal Highway (Via Regia) connecting the Eastern and Western part of the continent. It is believed that its founder was the Czech Duke Vratislaus, after whom Wrocław was named not only in Polish, but also in Czech (Vratislav), Latin (Wratislavia), and German (Breslau).

The first residents of Wrocław were the Silesians, who in the 9th–10th centuries settled on the Oder Plain around Mount Ślęża, which the Silesians considered a holy place. It is after these people that the entire region known today as Silesia (Śląsk) was probably named, with Wrocław as its historic capital.

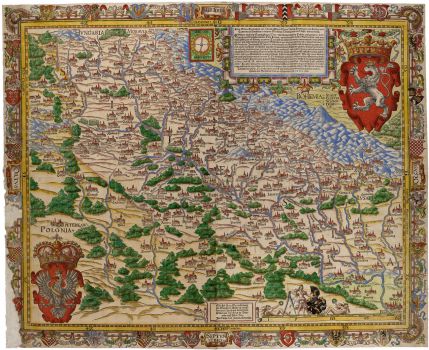

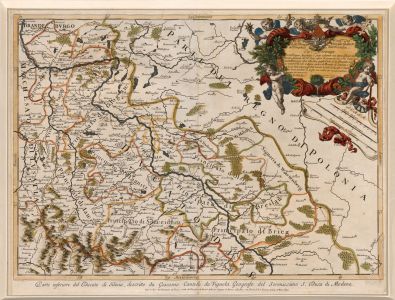

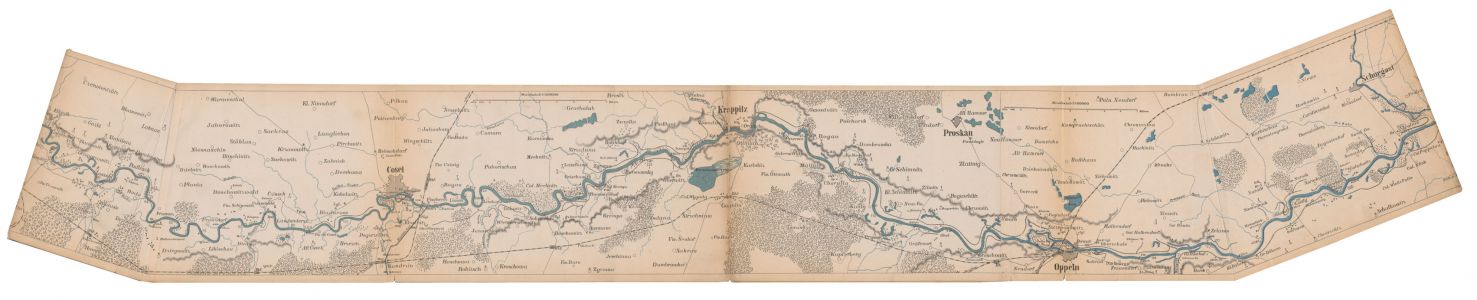

Silesia, when compared to the main European regions, has always been distinguishable by its geographical separation. The history of Silesia has shown that its natural boundaries are more enduring than any other boundaries, including even political divisions secured by treaties. That is because Silesia constitutes a clear and cohesive unit located within the upper watershed and the middle course of the River Oder, especially in terms of the climate, water conditions, landscape, geological structure and flora and fauna.

Upon entering the historical arena, Silesia has been the subject of disputes among Poland, the Czech Republic and Germany. Despite those disputes, the territorial division into duchies established in the Middle Ages constituted the basis of its administrative structure until the 18th century. The Partition of Silesia carried out by Austria and Prussia did not take into account the historic borders, and after the Congress of Vienna, Silesian Province was given new external borders and a modified administrative structure. According to the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles, Silesia was divided between Germany, Poland and Czechoslovakia. After 1945, the entire Lower Silesia region was incorporated into Poland, and Wrocław became the capital of the newly-established voivodeship.

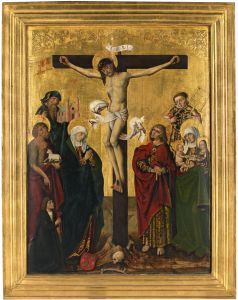

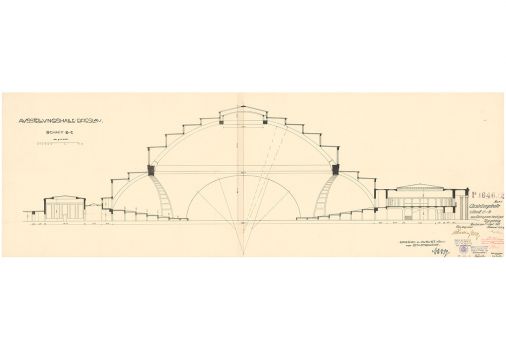

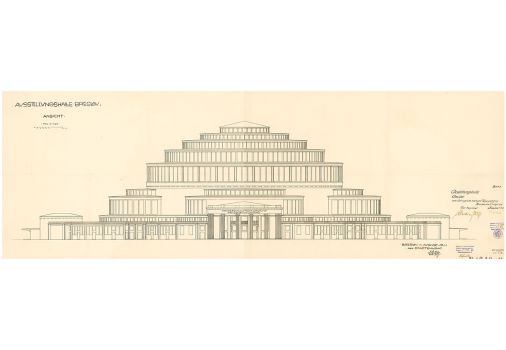

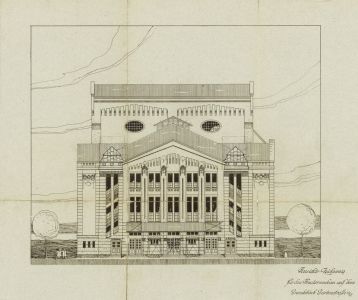

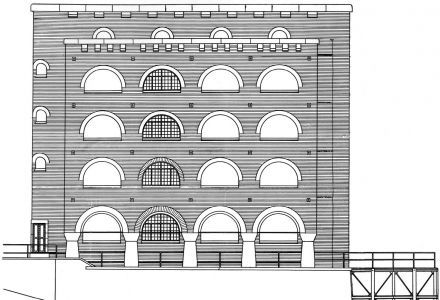

The city landscape of Wrocław was shaped over hundreds of years, and despite the scale of the destruction caused by the war in 1945 (affecting 70% of the city’s buildings and infrastructure ), many of its areas have preserved their historic character. This is due in major part to many reconstruction works that have been carried out, not to mention those that are still being carried out today. Therefore, we can find nearly all the main styles in European architecture in the city – from Romanesque remains, to Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, Classicism, Historicism, Art Nouveau and Modernism.

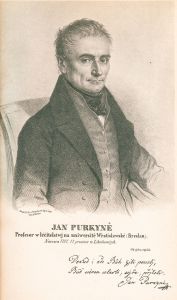

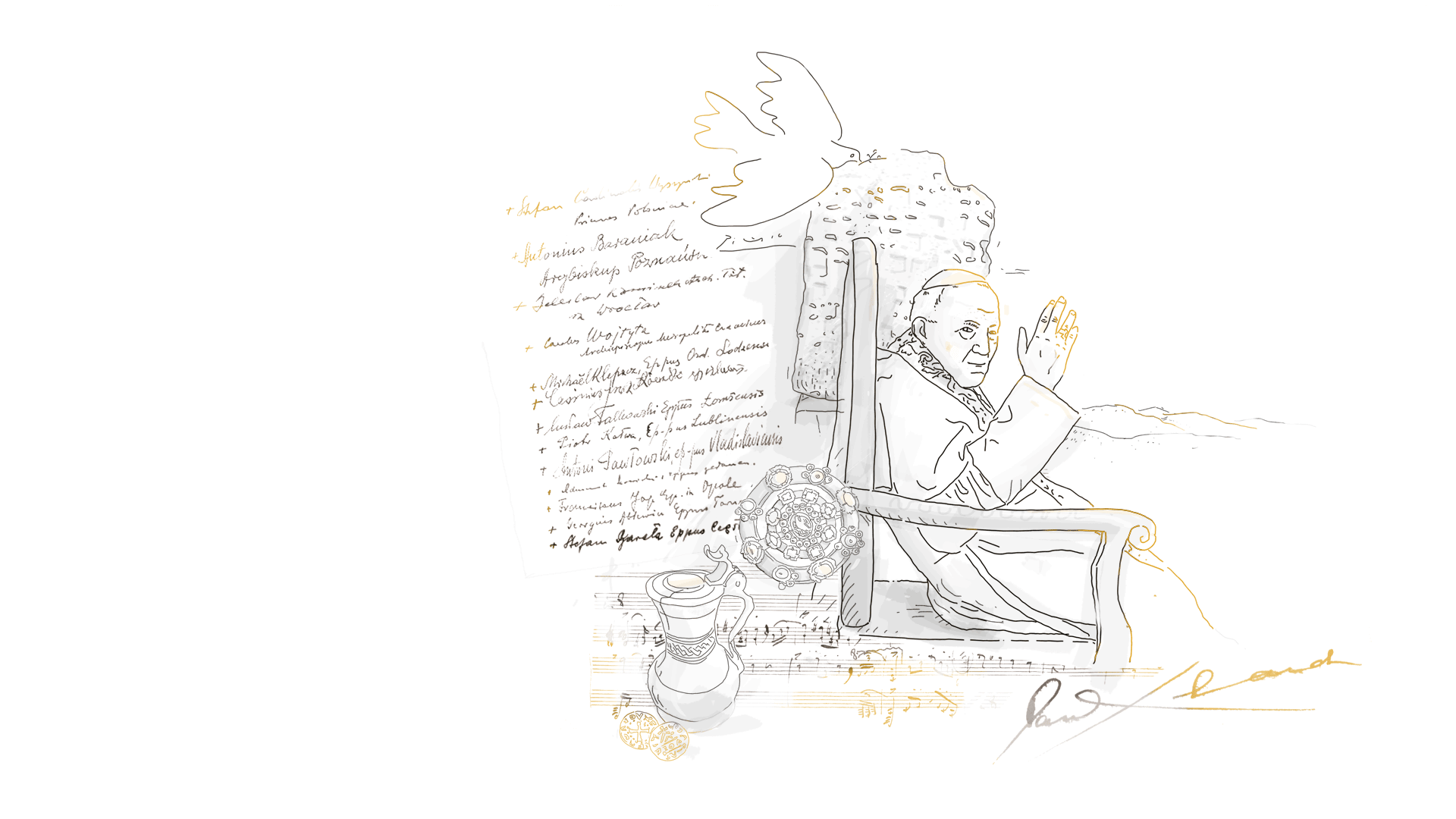

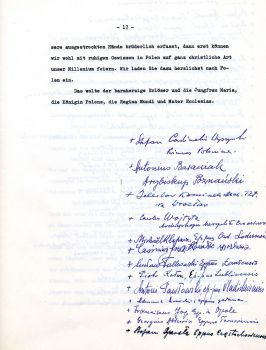

Dariusz Przybytek